03 - Electrical Enclosure Interiors

Essential Guide to Electrical Panels: What Every Home Buyer Should Know Before Making an Offer

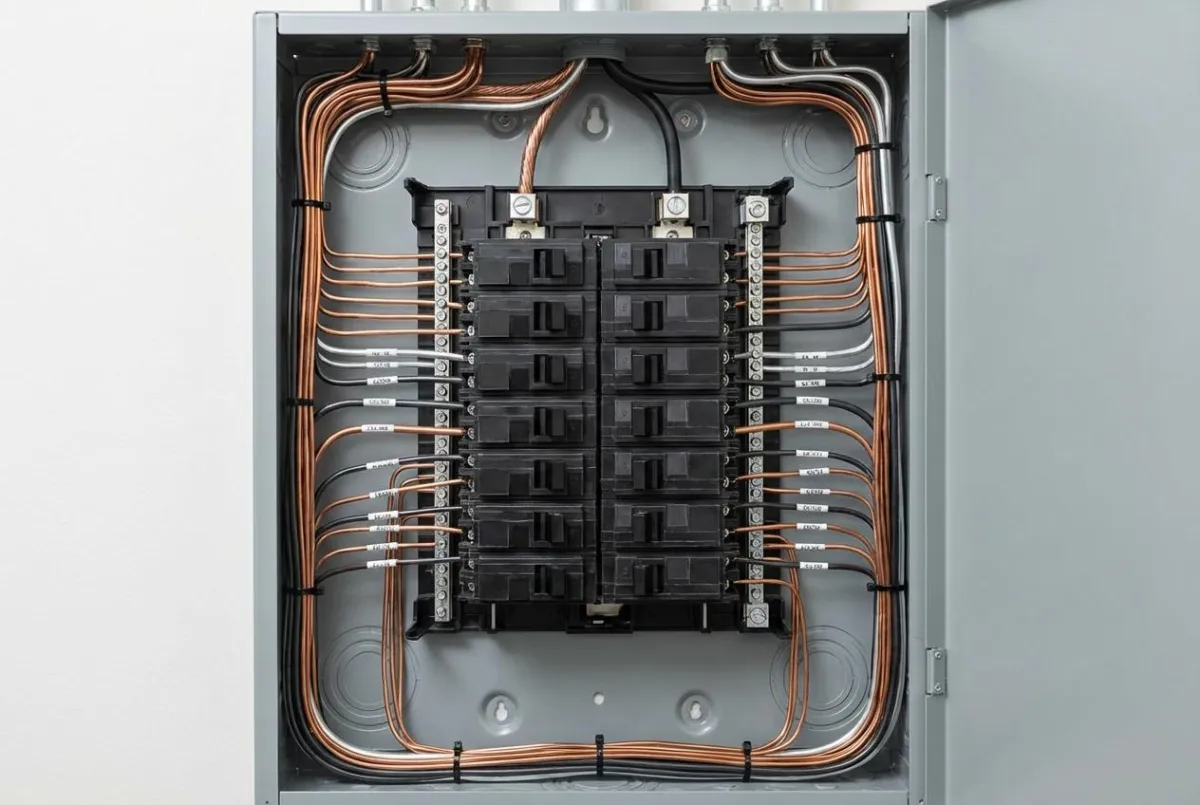

When you're shopping for a home, the electrical panel may seem like just another gray box on the wall. But as a home inspection expert, I can tell you that understanding what's behind that cover could mean the difference between a safe investment and a potentially dangerous money pit. Let me share the critical knowledge you need to evaluate a home's electrical system like a professional.

Why the Electrical Panel Matters More Than You Think

Your home's electrical panel is the heart of your electrical system. It's where overcurrent protection devices—either circuit breakers or fuses—work tirelessly to prevent electrical fires by interrupting power flow when things go wrong. These devices serve two vital purposes: they stop excess current that can overheat wires and ignite surrounding materials, and they shut down power during short circuits that can create dangerous sparks.

Understanding that most homes are built with combustible materials like wood makes the importance of proper electrical protection crystal clear. A malfunctioning or improperly configured electrical panel isn't just an inconvenience—it's a fire waiting to happen.

Fuses vs. Circuit Breakers: Understanding What You're Looking At

If You See a Fuse Panel

While Thomas Edison patented an early circuit breaker in the late 1800s, fuses remained the primary protection method in homes through the 1950s, with some installations continuing into the 1960s. If the home you're considering has a fuse panel, pay close attention.

Fuses work through a simple but effective principle: they contain a metal strip designed to melt when current exceeds safe levels. When that metal melts, power stops flowing and disaster is averted.

You'll encounter three main fuse types:

Edison Base (Type T) Fusesare the older round fuses that screw into holders. Here's the critical problem: all Edison base fuses have the same size base, meaning someone could easily screw a 30-amp fuse into a circuit designed for only 15 amps. This "overfusing" allows dangerous amounts of current to flow through undersized wires—a serious fire hazard. If you see Edison base fuses, or worse, a penny or other metal object substituted for a fuse, consider this a major red flag requiring immediate electrician evaluation.

Type S Fusessolved the substitution problem by giving each amperage rating a different size base. If the home has Edison base holders, adapters can be installed to convert them to the safer Type S system.

Cartridge Fusesare cylinder-shaped and often found in older service equipment or disconnect boxes for HVAC systems. Larger 100-amp cartridge fuses typically have blade connectors on both ends.

Here's a useful tip: fuses are color-coded by amperage—blue or purple for 15 amps, orange or red for 20 amps, green or yellow for 25 amps, green for 30 amps. Labels sometimes fade over time, but you can often find the rating stamped inside the fuse or on the case.

Bottom line on fuses:Most fuse panels are past their service life. If you're serious about a home with fuses, budget for a complete electrical panel replacement.

Modern Circuit Breaker Panels

Circuit breakers became common in homes during the 1960s and now dominate the residential market. Modern circuit breakers are sophisticated devices that protect against both types of electrical faults using two technologies:

Magnetic-trip technologydetects short circuits through the intense magnetic field they generate

Thermal-trip technologydetects overcurrent by sensing the heat it produces

Today's residential circuit breakers combine both technologies, which is why they're called thermal-magnetic-trip circuit breakers. Some older breakers use only one technology and may not provide complete protection—another reason to be cautious with older electrical systems.

Circuit breakers are electromechanical devices with electronic and mechanical components, giving them a finite service life typically estimated at 30 to 50 years. Many experienced inspectors recommend replacing entire panels and breakers older than 50 years because they may no longer function properly when you need them most.

Critical Safety Features You Should See

Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCI)

GFCI protection is your defense against electrical shock in areas where water and electricity might meet. These devices monitor current flow and trip when they detect even a small imbalance—about 6 milliamperes—indicating electricity is taking an unintended path, possibly through a person.

When touring a home, verify that GFCI protection exists in these locations:

Kitchen countertop outlets

All bathroom outlets

Garage outlets

Laundry room outlets

Unfinished basement outlets

Outdoor outlets

Crawl space outlets

Unfinished detached building outlets

Dishwasher circuit (required since 2014)

GFCI requirements evolved over decades, starting in the 1970s with bathrooms, garages, and outdoor outlets. Kitchen countertops were added in the 1990s, and laundry areas in the 2000s. If a home you're considering lacks GFCI protection in these areas, factor in the cost of upgrades.

Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters (AFCI)

While GFCIs protect people from shock, AFCIs protect your home from fire. These devices detect dangerous arcing—sparking caused by damaged wires, loose connections, or deteriorating insulation within walls.

Modern building codes require AFCI protection for most 15 and 20-amp, 120-volt circuits throughout the home. The main exceptions are bathrooms, laundry rooms, basements, crawl spaces, garages, and outdoor circuits.

AFCI requirements began in the early 2000s for bedroom outlets and expanded to most other circuits by the late 2000s. You'll find two types: the older branch circuit/feeder type (no longer permitted) and the current combination type that detects both parallel faults (between wires) and series faults (along a single wire).

If you're looking at a home built or renovated after the early 2000s, verify that appropriate AFCI protection is installed. Its absence in a newer home could indicate unpermitted electrical work.

Red Flags Inside the Electrical Panel

When a qualified inspector opens the panel cover, here are the critical defects to watch for:

Mismatched Circuit Breakers

Panelboards and circuit breakers are engineered as matched systems. A circuit breaker from a different manufacturer—even if it seems to fit—may not function properly. If you see brands that don't match the panel manufacturer's label, insist on electrician verification that the correct breakers are installed.

Oversized Breakers for Wire Size

One of the most common and dangerous defects is a circuit breaker rated for more current than the wire it protects can safely carry. The fundamental rule for copper wire branch circuits is:

14-gauge wire: maximum 15-amp breaker

12-gauge wire: maximum 20-amp breaker

10-gauge wire: maximum 30-amp breaker

8-gauge wire: maximum 40-amp breaker

6-gauge wire: maximum 55-amp breaker

There are exceptions for air conditioning systems and other specific equipment, but if you see a 20-amp breaker protecting 14-gauge wire, you're looking at a fire hazard. The oversized breaker allows current that will overheat the undersized wire.

This defect often occurs when someone installs a new, more efficient air conditioning condenser without updating the circuit breaker to match the new equipment specifications shown on the condenser label.

Multiple Wires Under One Connection (Double Tapping)

Unless specifically approved by the manufacturer, each circuit breaker terminal should connect to only one wire. "Double tapping"—cramming two wires under one terminal—creates multiple hazards. Wires can work loose over time, creating dangerous arcing and potentially leaving a circuit unprotected or improperly protected by an oversized breaker.

The exception: Some manufacturers, notably Square D's Homeline series for 15, 20, and 30-amp breakers, specifically design terminals to accept two same-sized wires using a special double saddle. But this must be explicitly stated in the manufacturer's instructions.

Rust and Corrosion

Rust inside an electrical panel signals water infiltration, which increases electrical resistance and fire risk. Any significant rust or corrosion warrants immediate professional evaluation.

Missing Handle Ties on 240-Volt Circuits

Circuits operating at 240 volts (like those for electric dryers, ranges, and central air conditioners) require both breakers to trip simultaneously. They must be connected with approved handle ties—never improvised connections using wire, nails, or other makeshift materials.

Missing Knockouts and Cover Plates

Every opening in the electrical panel must be properly covered. Missing knockouts or gaps create shock hazards and allow pests, dust, and moisture into the panel. Makeshift covers using tape, cardboard, or other non-approved materials are unacceptable.

Improper Cable Connections

Every cable entering the panel must be secured with proper cable clamps or enter through conduit connected with appropriate fittings. Loose cables can shift over time, creating dangerous situations.

Unlabeled Circuits

Each circuit should be clearly labeled to identify what it controls. Labels like "Billy's room" don't count—they become meaningless when occupants change. Proper labels specify function and location in permanent terms.

Too Many Breakers

Every panelboard has a maximum number of circuits it's designed to serve, clearly stated on the label. Exceeding this number creates overheating risks. The label also specifies which slots, if any, can accept half-height (tandem) breakers. Violations indicate amateur electrical work and potential safety compromises throughout the system.

Panel Location and Access: Often Overlooked but Critical

Even a perfectly functional panel becomes a safety liability if it's not properly accessible. When evaluating a home, verify these requirements:

Adequate Working Space:The area in front of the panel must provide at least 36 inches of depth, 30 inches of width, and 78 inches of height, measured from the floor. The door must swing open at least 90 degrees. Panels crammed into tight corners or blocked by shelving, furniture, or storage violate safety codes and make emergency shutoff difficult.

Proper Location:Electrical panels don't belong in bathrooms, clothes closets, storage rooms, or above stair steps (though stair landings are acceptable if working clearances are met). Indoor panels should have lighting nearby.

Appropriate Height:Breaker handles shouldn't be more than 79 inches above the floor when in the "on" position. There's no minimum height requirement, but panels installed very low create their own accessibility challenges.

Readily Accessible:You should be able to reach the panel without moving objects, climbing over obstacles, or using ladders. Panels hidden behind mirrors, pictures, or furniture don't meet this standard.

Reserved Space:The area directly above and below the panel is reserved exclusively for electrical components. Plumbing pipes, HVAC ducts, and other systems shouldn't intrude into this space.

Special Considerations: Split-Bus Panels

A few older homes have split-bus panels, recognizable because they lack a single main breaker. Instead, electricity for standard branch circuits flows through a breaker on an upper bus. These panels have slots for up to six 240-volt circuits on the upper bus, with one feeding the lower bus.

While not inherently dangerous if properly maintained, split-bus panels are outdated. Their age alone—typically 40-60 years—suggests replacement should be on your radar.

What This Means for Your Home Purchase

As you tour potential homes, the electrical panel offers a window into both the home's safety and its maintenance history. Here's how to use this knowledge:

For newer homes (built after 2000):Verify appropriate AFCI and GFCI protection exists where required. Missing protection might indicate unpermitted DIY work—a red flag suggesting other hidden problems.

For homes built 1960-2000:Check for circuit breaker panels (preferred over fuses), adequate GFCI protection in moisture-prone areas, and absence of obvious defects like double-tapped breakers or mismatched brands. Panels approaching 40-50 years old should be on your replacement radar.

For homes built before 1960:Expect significant electrical upgrades to be necessary or recently completed. Fuse panels, outdated wiring methods, insufficient circuit capacity for modern loads, and absence of required safety devices all point to major renovation needs. Budget accordingly.

For any home:Insist on professional inspection of the electrical panel interior by a qualified inspector who understands these safety issues. If the inspector identifies concerns, get estimates from licensed electricians before finalizing your offer. Electrical panel replacement typically costs $1,500-$3,000, but extensive whole-house rewiring can run $8,000-$15,000 or more.

The Bottom Line

The electrical panel is far more than a mundane utility box. It's a sophisticated safety system protecting your family and your investment from fire and shock hazards every single day. Understanding what you're looking at—and knowing which red flags demand immediate attention—empowers you to make informed decisions and negotiate effectively.

Don't let a seller's fresh paint and staged furniture distract you from this critical system. A home with a properly maintained, code-compliant electrical panel gives you peace of mind. A home with an outdated, defective, or improperly modified panel gives you a negotiating point—or a reason to walk away.

Your home inspector is your expert advocate in evaluating these complex systems. When they recommend electrical evaluation or upgrades, take it seriously. The few hundred dollars you spend on professional assessment and the thousands you might invest in upgrades pale in comparison to the cost of fire damage, injury, or loss of life.

Make the electrical panel a priority in your home-buying journey. Your future self—safely enjoying your new home—will thank you for the diligence.