02 - Grounding and Bonding

The Home Buyer's Essential Guide to Electrical Grounding and Bonding: What Every Smart Buyer Must Know

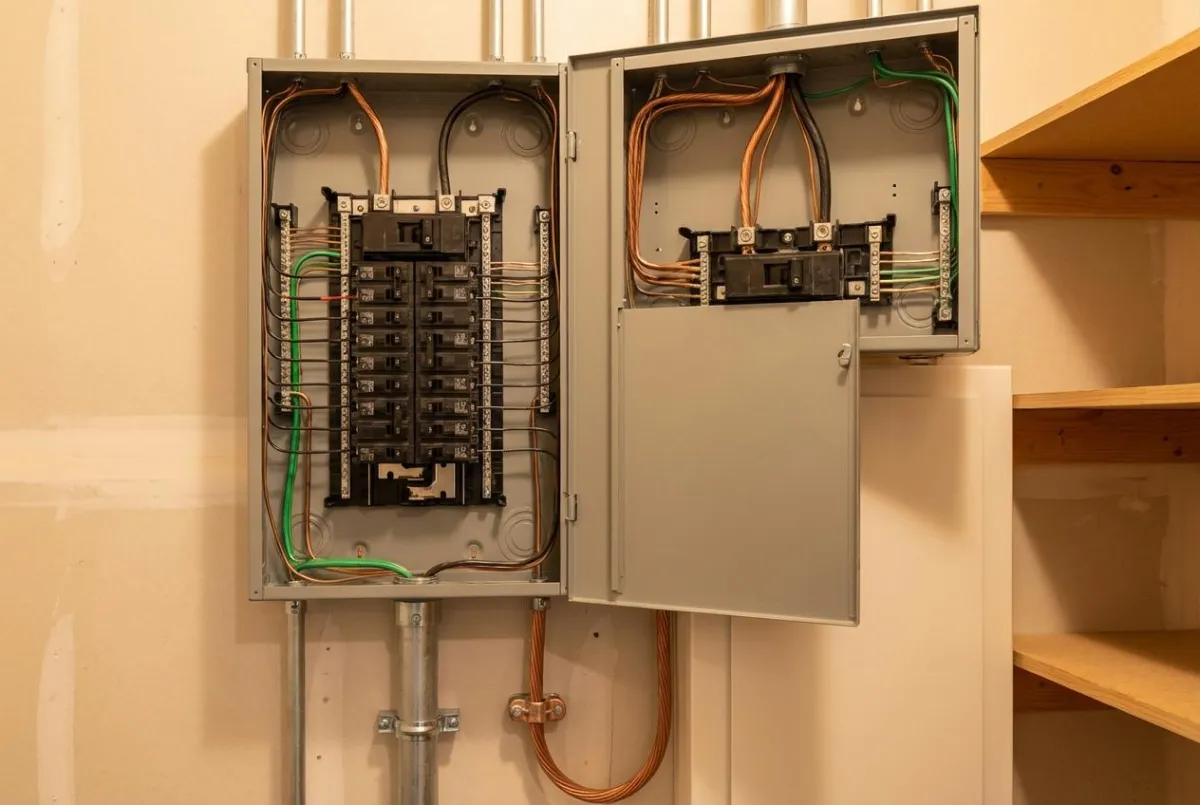

When you're shopping for a home, you'll likely focus on the kitchen finishes, the master bathroom, and whether the basement is finished. But there's a critical safety system hiding behind your walls that deserves just as much attention: the electrical grounding and bonding system. As a home inspector, I've seen countless buyers overlook this vital component, only to face expensive repairs or serious safety hazards after closing. Let me share what you absolutely need to know before you sign on that dotted line.

Understanding the Invisible Shield: Grounding vs. Bonding

First, let's clear up a common confusion. Grounding and bonding are two distinct systems, though they work together to keep you safe. Think of grounding as your home's electrical equipment protector, while bonding is your personal bodyguard. Neither system operates during your home's normal daily electrical use—they're emergency responders that spring into action only when something goes wrong.

Why Grounding Matters to You

Imagine lightning strikes near your neighborhood's utility transformer, or a high-voltage wire falls onto the service lines feeding your home. Without proper grounding, that massive surge of electricity has nowhere to safely escape. It will find a path—potentially arcing through wire insulation to metal water pipes, destroying the motor in your expensive HVAC system, or frying your brand-new smart TV. In worst-case scenarios, it can cause fires or electrocution.

The grounding system acts like a whole-home surge suppressor. It intercepts these dangerous voltage surges and shunts them safely into the earth, limiting their ability to damage your property or harm your family. While even the best grounding system can't always prevent damage from a direct lightning strike, a properly installed system dramatically reduces your risk.

Bonding: Your Personal Safety Net

While grounding protects your equipment, bonding protects you and your family. Here's how it works: bonding intentionally connects together all metal components that could potentially carry electricity but aren't supposed to. This creates a permanent, low-resistance pathway that can conduct any accidental electrical current back to its source.

Let me paint a picture of why this matters. Suppose a rodent chews through the insulation on an electrical wire that's touching your copper water pipe. If that pipe is properly bonded, the circuit breaker will immediately trip, cutting power and eliminating the hazard. But if the pipe isn't bonded, that pipe remains electrified—waiting silently until someone touches a metal faucet or showerhead. At that moment, the person becomes the return path for the electricity, with potentially fatal consequences.

What "Low Resistance" Really Means (And Why It Could Save Your Life)

The "low resistance" part of bonding isn't just technical jargon—it's the difference between life and death. A properly bonded system must have low enough resistance to allow enough current to flow to trip the circuit breaker immediately.

Here's a real-world example: If a bonding clamp is loose or installed on a painted or rusted surface, it might create 10 ohms of resistance. Using basic electrical principles, 120 volts divided by 10 ohms equals 12 amps. That 12-amp current won't trip a standard 15-amp circuit breaker, leaving the fault energized indefinitely. Meanwhile, 12 amps is more than enough to kill a person who touches that electrified surface.

When the bonding is properly installed with minimal resistance—say 0.5 ohms—that same 120 volts creates 240 amps of current, which immediately trips the breaker. Yes, you might still get shocked for a fraction of a second, but the circuit clears before serious harm occurs.

Busting Common Electrical Myths

As a home inspector, I constantly encounter two persistent myths that prevent people from understanding these critical systems.

Myth One: Electricity wants to return to ground. Actually, electricity wants to return to its source—the utility transformer and ultimately the power generation station. When all bonded metal is connected by a low-resistance path to the utility's grounded wire, that becomes the preferred return path, not the earth itself.

Myth Two: Electricity takes the path of least resistance. In reality, electricity takes all available paths simultaneously. The current flowing through each path depends on the resistance in that path. This is precisely why proper bonding with low resistance is so critical—it ensures most of the current flows through the safe, intended pathway rather than through you.

What to Look for When Touring Homes

Now that you understand the "why," let's discuss the "what." When you're walking through potential homes, here's what you need to examine (or have your home inspector examine closely):

The Grounding Electrode System

Every home needs at least one grounding electrode—essentially a direct connection to the earth itself. Common types include:

Concrete-encased electrodes (Ufer grounds): At least 20 feet of rebar or bare copper wire encased in the home's concrete foundation

Ground rods: Galvanized steel or copper-coated steel rods driven at least eight feet into the ground

Metal water service pipes: The underground metal water line entering the home, if it contacts earth for at least ten feet

In older homes, you might find just one electrode. Newer homes require multiple electrodes bonded together. If the home has a metal water service pipe, it must be included in the grounding system regardless of what other electrodes exist.

The grounding electrode conductor (GEC)—the wire connecting these electrodes to your electrical system—should be substantial. For service panels rated 150 amps or greater, look for at least #6 AWG copper wire. For 200-amp or greater service with concrete-encased electrodes, you need #4 AWG copper. Smaller 125-amp services can use #8 AWG copper.

In newer construction, the connection to a water pipe electrode must occur within five feet of where the pipe enters the home. This isn't arbitrary—it ensures the connection happens before any plastic fittings or removable components that could interrupt the grounding path.

Critical Connection Point

The grounding electrode conductor must connect to the utility's grounded (neutral) wire at an accessible location between where power enters the home and the main service panel. This is the only point where this connection should occur. Any additional grounding connections downstream can create dangerous unintended current paths, potentially energizing metal components throughout your home even under normal operating conditions.

Bonding Requirements Throughout the Home

Here's a simple rule: if it's metal and anywhere near electrical wiring, it probably needs to be bonded. When inspecting a home, verify bonding for:

Metal water distribution pipes throughout the home

Gas pipes and distribution systems

Electrical conduit and equipment cabinets

Metal framing and sheathing materials

HVAC ductwork

Cable TV and satellite coaxial cables

All metal parts of the electrical service and distribution system

Every bonding connection must be physically secure and provide excellent electrical conductivity. This means connections must be tight, made to clean metal surfaces free of paint, rust, or other contaminants. Any interruption in metal piping—such as water meters, pressure regulators, water softeners, or plastic fittings—requires a bonding jumper wire to bridge the gap and maintain the low-resistance path.

Red Flags Every Home Buyer Should Recognize

As you evaluate homes, watch for these common defects that indicate problems with the grounding and bonding systems:

At the Grounding Electrodes:

Damaged, disconnected, or loose grounding electrode conductors where they attach to ground rods or other electrodes

Undersized grounding wires (the conductor should match the recommendations above based on service size)

Missing or loose grounding clamps

Clamps attached to corroded, painted, dirty, or otherwise contaminated surfaces that prevent good electrical contact

Improperly spliced grounding conductors (splices require listed compression connectors or welding—never soldering)

In the Distribution System:

Metallic conduit connected with plastic fittings, which interrupts the bonding pathway

Grounding connections to underground water pipes located more than five feet from where the pipe enters the home (in newer construction)

Missing, loose, or corroded metal conduit connections

Absent or loose bonding connections to metal water pipes

At Interruptions in Metal Piping:

Missing bonding jumpers around water meters—one of the most common defects I encounter

No jumpers around water pressure regulators, water softeners, water filters, or similar components

For homes with CSST (corrugated stainless steel tubing) gas lines, missing bonding at the first metal gas pipe or fitting after the gas meter—this is a critical fire safety issue

For Communications Systems:

Improper or missing bonding connections for telephone, cable TV, or satellite systems

Special Concern: CSST Gas Tubing

If you're looking at a home with CSST gas tubing (the flexible yellow or black corrugated stainless steel tubing used for gas distribution), pay special attention to the bonding. CSST is particularly vulnerable to lightning strikes and electrical faults. Without proper bonding directly at the first metal gas pipe or fitting after the meter, a lightning strike can puncture the CSST, releasing gas inside your walls and creating an extreme fire and explosion risk. This is non-negotiable—if CSST isn't properly bonded, it must be corrected before you close on the home.

Why This Matters for Your Offer and Negotiations

Grounding and bonding defects aren't cosmetic issues you can ignore or postpone. They represent genuine safety hazards that put your family and your investment at risk. When your home inspector identifies these problems, you have several options:

Request repairs before closing: The seller corrects all grounding and bonding defects prior to transfer of ownership

Negotiate a price reduction: Get a credit to handle the repairs yourself with a qualified electrician

Walk away: If the defects are extensive and indicate poor overall electrical maintenance, it might signal deeper problems with the home

Remember that many grounding and bonding defects are relatively inexpensive to fix when caught early but can lead to catastrophic equipment damage, fires, or personal injury if left unaddressed. A few hundred dollars in bonding jumpers and proper connections is trivial compared to replacing a fried electrical panel, repairing fire damage, or worse.

The Bottom Line for Home Buyers

The grounding and bonding systems in your potential new home are invisible most of the time, but they're working continuously to protect you from electrical hazards. A properly installed system channels dangerous voltage surges safely to earth and ensures that any electrical faults immediately trip circuit breakers before someone gets hurt.

When you're touring homes, don't just admire the granite countertops and hardwood floors. Look at the electrical panel. Trace the grounding electrode conductor to its connection point. Check for bonding jumpers around the water meter. Ask your home inspector to pay particular attention to these systems and clearly document any deficiencies in your inspection report.

These systems represent the difference between a safe home and a hazardous one. As someone who has inspected thousands of homes and seen the consequences of electrical failures, I can tell you with absolute certainty: a beautiful kitchen isn't worth much if your home's electrical system can't protect your family.

Insist on proper grounding and bonding. Your family's safety depends on it.

When shopping for a home, always hire a qualified, experienced home inspector who understands electrical systems and can identify grounding and bonding defects. A thorough electrical inspection is one of the most valuable investments you can make in your home-buying journey.